A substantial proportion of solid by-products resulting from fish processing are discarded, comprising bones, heads, tails, and skins. These by-products pose a significant environmental concern due to their potential for contaminating water bodies. However, these by-products also constitute a valuable source of high-quality proteins, including collagen, a protein that holds particular interest in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries (Karayannakidis and Zotos, 2016). Currently, collagen is mainly extracted from pig and cattle hides and bones by enzymatic pretreatments (Almeida et al., 2013). However, an inherent advantage of collagen of marine origin in addition to its protein value is the compatibility with religious beliefs, as it avoids the use of collagen from bovine and porcine sources, which are not consumed among Hindus and Muslims, respectively. Global fish production reached 175 million tons in 2017 and is projected to reach over 194 million tons by 2026 (Gaikwad and Kim, 2024).

At the production scale approximately 25% of the total weight of fish is utilized by the fish processing industry, while the remaining 75% is classified as waste by-products among which skeletons, bones, heads, guts, tails skins and other fishery discards are included (Srikanya et al., 2017). On the other hand, the utilization of fish waste for collagen production has the potential to provide high-value protein and mitigate environmental concerns, thus enhancing the economic prosperity of fish processing industries (Ferraro et al., 2010). Advantageously collagen from fish discards has higher bioavailability and absorption efficiency, approximately 1.5 times higher compared to its alternative of bovine and porcine origin (Sripriya and Kumar, 2015).

Despite these advantages, fish collagen has some drawbacks, such as low mechanical strength, amino acid content, biomechanical stiffness and melting point. Other than collagen, hydrolysates and their peptides have also gained much attention as a functional ingredient due to their various health benefits (Jamilah et al., 2013). Techniques such as acid-soluble isolation (ASC) and pepsin-soluble isolation (PSC) have been used for the extraction of collagen (Hamdan and Sarbon, 2019). Enzymatic treatment by hydrolysis is the best method revealed for the extraction of collagen from fish because it tends to remove the non-helical ends and increase the solubility of collagen molecules and therefore increasing the yield of the extracted material (Ahmed and Chun, 2018).

The field of collagen extraction techniques has witnessed a progression from conventional methods to the incorporation of ultrasound and CO2 technology ((Lu et al., 2023; Sousa et al., 2020). Nevertheless, acid and enzymatic extractions remain the most prevalent techniques (Cao et al., 2022; Hou and Chen, 2023; Carpio et al., 2023). Acetic acid has been employed due to its superior efficacy in comparison to other acids, while pepsin has been utilized for enzymatic extraction due to its efficacy in maintaining the structural integrity of collagen during the digestive process (Kiew and Don, 2013).

A number of studies have been conducted over time to ascertain the efficacy of various extraction techniques. For instance, Giménez et al. (2005) and Jayasundara et al. (2022) investigated the solubility of yellowfin tuna skin collagen in lactic acid, while Khiari and Rico (2011). Examined the extraction of gelatin from mackerel heads using organic acids such as acetic acid, Additionally, Yu et al. (2014) conducted an acid solubilization extraction of collagen from skipjack tuna vertebrae and skull. Similarly, collagen was extracted from yellowfin tuna via a surface reaction Nguyen et al. (2021); Blanco et al. (2019). Furthermore, acid hydrolysis was utilized in the extraction of collagen from bonito sarda and corvina (Valderrama et al., 2021). Accordingly, the objective of this study is to quantify the concentration of hydroxyproline as an indicator of collagen content in the vitreous humor of yellowfin tuna. In addition to the protein and amino acid composition, the study will determine whether the extraction process at different concentrations of pepsin allows for confirmation of the hypothesis of the presence of collagen in this fishery by-product. The findings of this study will facilitate new methodologies for obtaining collagen from tuna eyes, which will have direct applications in the utilization of fishery by-products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Ethical approval

The research committee of the Universidad Laica Eloy Alfaro de Manabí provided the study's investigators with a set of guidelines for the manipulation of tuna eyes (Memo: DPCRI-2024-0724-OF) which were strictly followed.

2.2 Study area

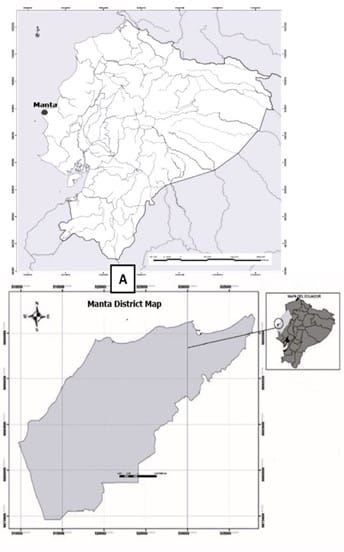

The eyes of yellowfin tuna were procured from the seafood landing area of the Esteros market, situated within the Ecuadorian central coast of Manta city, Manabí province, Ecuador (Figure 1).

Figure 1 (A). The subsequent map delineates the geographical location of the district of Manta in Manabí, Ecuador (B). The reception area of seafood from the esteros market in the city of Manta was the site where the sampling was conducted.

Figure 1 (A). The subsequent map delineates the geographical location of the district of Manta in Manabí, Ecuador (B). The reception area of seafood from the esteros market in the city of Manta was the site where the sampling was conducted.

2.3 Fish sample selection

Specimens with a weight range of 40-60 pounds were selected. Transverse incisions were made in the skull of the specimens, taking care to avoid damaging the eye socket, until the eyeball was fully separated. The total quantity of the sample obtained was 3.8 kg. Subsequently, the samples were stored in a polypropylene cooler with ice and subsequently frozen at -20 °C. The maximum storage period was one month. The reagents utilized were of food and analytical grade. The trans-4-hydroxy-L-proline 99% was procured from Labsupply S.A. (Geel, Belgium) and Thermo Fisher Scientific. Pepsin was obtained from Innovating Science, S.A. (Rochester, New York) and was diluted 1:3000. Ferrous sulfate heptahydrate, 99% (Eisen-Golden S.A., Dublin, California). Cupric sulfate pentahydrate, 99% pure, was procured from Biopharm S.A. (Eppelheim, Germany). P-Dimethylamino benzaldehyde 99%, HiMedia S.A (Mumbai, India). Sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, n-propanol 99%, Fischer Chemical S.A (Hampton, USA). Sodium hydroxide pellets, Merck S.A (Darmstadt, Germany). Acetic acid, food grade, Woeberd S.A. 5% v/v (Springfield, USA).

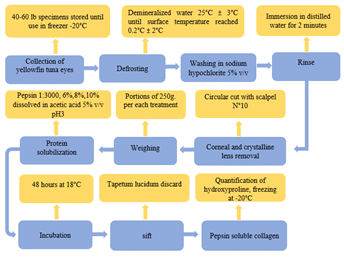

2.4 Sample preparation

The samples of yellowfin tuna eye were thawed by immersion in demineralized water at a temperature of 25.0 ± 3.0 °C until the surface temperature reached 2.5 ± 2.0 °C. Subsequently, the samples were immersed in 5% v/v sodium hypochlorite for five minutes and rinsed with distilled water for two minutes. A circular incision was made with a #10 scalpel to remove the cornea and lens, thus facilitating vitreoretinal-pepsin interaction. The eyes were weighed and divided into portions of 250 g ± 0.50 for each treatment.

2.5 Extraction of pepsin soluble collagen

The extraction of collagen was conducted in accordance with the methodology described by Ong et al. (2021) with certain modifications (Figure 2). A total of 250 g ± 0.5 of yellowfin tuna eyes were incubated with 300 mL of pepsin (6%, 8%, subsequently, the samples were strained through 8-micrometre mesh, with the tapetum lucidum discarded (Ghazwan and Janabi, 2015). Ultimately, the solution was classified as pepsin-soluble collagen. The experiments were conducted in triplicate at room temperature (18 °C) as recommended by Rashidy et al. (2015).

2.6 Quantification of hydroxyproline

The concentration of hydroxyproline was determined by the colorimetric method (Miyadda and Tappel, 1956). One milliliter of collagen was hydrolyzed with one milliliter of 6 N hydrochloric acid for three hours at 100 °C. In 20-mL test tubes, 1 mL of the hydrolyzed mixture was diluted by the addition of distilled water at a ratio of 1:20. Subsequently, 1 mL of the aforementioned dilution was combined with 1 mL of 0.01 M cupric sulfide, 1 mL of 2.5 N sodium hydroxide, and 1 mL of 6% hydrogen peroxide. Subsequently, 1 mL of the aforementioned dilution was combined with 1 mL of 0.01 M cupric sulfate, 1 mL of 2.5 N sodium hydroxide, 1 mL of 6% hydrogen peroxide, and 0.1 mL of 0.05 M ferrous sulfate solution, and the mixture was stirred manually for 2 minutes until gas bubbles emerged.

Figure 2. Process of extracting collagen from the vitreous humor of yellowfin tuna.

Figure 2. Process of extracting collagen from the vitreous humor of yellowfin tuna.

Subsequently, 4 mL of 3 N sulfuric acid and 2 mL of 5% p-dimethylamino benzoaldehyde solution dissolved in 99% n-propanol were added and heated at 70 °C for 16 minutes in a water bath. A heat shock was conducted in an ice bath for five minutes. The resulting color was then measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 540 nm (Jenway 6320D, USA). A calibration curve was constructed using nine standard solutions of trans-4-hydroxy-L-proline, prepared in advance and containing concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 μg/mL. The resulting standard curve was found to be Y = 0.006. The resulting equation was 5x + 0.0025, with an R2 value of 0.9758. The percentage of hydroxyproline and collagen was determined using the following equation, as proposed by (Lydrup and Fernö, 2003).

In this context, df represents the dilution factor, 10 denotes the initial hydrolysate concentration, and 7.46 serves as the conversion factor.

The calculation of the yield was based on the following equation (Chuaychan et al., 2015).

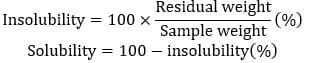

2.7 Solubility

The previously extracted collagen was subjected to a 72-hour drying process at 30 degrees Celsius and subsequently employed for solubility determination. A solution of 0.5 g of dried collagen in 5 ml of distilled water was prepared and subjected to centrifugation at 3,200 rpm for 10 minutes at 22 °C (Shon et al., 2011). The supernatant was recovered, dried at 100 °C for 5 minutes, and the final weight was recorded. The solubility was determined using the following equation (Nurilmala et al., 2019).

2.8 Tricine SDS-PAGE

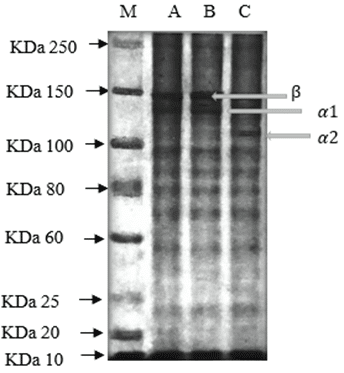

Tricine-SDS-PAGE was carried out in accordance with the methodology outlined by Laemmli et al. (1970). To 1 mL of the sample, 20 µL of 2-mercaptoethanol was added and heated in a boiling water bath at 100 °C for three minutes. The concentration of the separation gel was 16%. Each sample was loaded into a sample well using a micro syringe and electrophoresed at constant voltage (30 mV) until all samples entered the stacking gel. Thereafter, constant voltage (100 mV) was applied until the end of the electrophoresis process. Subsequently, the gel was fixed with a solution of 100 mM ammonium acetate dissolved in methyl alcohol/acetic acid (5/1, v/v) for a duration of two hours. Thereafter, 0.025% (w/v) Coomassie blue G-250 in 10% acetic acid was applied for a further two hours, after which the gel was stained with 10% acetic acid (v/v). Band intensities on the gel were analyzed using the Bio-Rad Image Lab software with high molecular weight protein markers, and the resulting images were subsequently photographed.

2.9 Protein composition

The protein composition was determined in accordance with the AOAC (2023) reference method. The total protein content and volatile basic nitrogen were determined by the Kjeldahl method, while the fat percentage was determined by gravimetry subsequent to hydrolysis with hydrochloric acid and extraction of the fat with petroleum ether, using the Soxhletec System. The pH was determined by electrometry with a high-precision pH meter (model GLP 22 Crison, Barcelona, Spain).

2.10 Amino acid profile

Amino acid characterization was conducted using an automatic amino acid analyzer (HITACHI L-8900 Amino Acid Analyzer, Tokyo, Japan) in accordance with the methodology described by Yang et al. (2007).

2.11 Statistical analysis

All experiments and analytical measurements were conducted in triplicate, and the resulting data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences were identified through the application of ANOVA (P<0.05) and Tuckey's multiple range analysis (P<0.05), utilizing the Info-Stat statistical software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Hydroxyproline quantification

The 8% pepsin treatment had the highest hydroxyproline concentration (2.62 mg/g ± 0.62), followed by the 6% (2.51 mg/g ± 0.27) and 10% (2.36 mg/g ± 0.27) treatments. However, there were no significant differences (P>0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Hydroxyproline content at different pepsin concentrations. Lowercase letters indicate that there are not significant differences between treatments (P>0.05).

Figure 3. Hydroxyproline content at different pepsin concentrations. Lowercase letters indicate that there are not significant differences between treatments (P>0.05).

As demonstrated in this work, the findings of Ignat’eva et al. (2007) indicate that pepsin concentration does not influence hydroxyproline concentration. The hydroxyproline content has been reported to range from 2.60 mg/g in the extraction of type IV collagen from sheep crystalline, as documented by other authors, such as Lino-Sánchez et al. (2023). Conversely, the hydroxyproline concentration in obtaining collagen from three genetic lines of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) has been reported to range from 0.025 mg/g of hydroxyproline Additionally Liu et al. (2020). Reported values of 1.14 mg/g of hydroxyproline in the skin of the blue shark (Prionace glauca). The findings for hydroxyproline are comparable to those observed in yellowfin tuna (T. albacares) (3.08 mg/g hydroxyproline) and bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) (2.99 mg/g hydroxyproline) in the assessment of amino acids conducted in muscle tissues through solubilization with pepsin (Peng et al., 2013). Conversely, a higher concentration of hydroxyproline (8.2 mg/g) was observed in bigeye (T. obesus) skins in collagen extraction by isoelectric precipitation (Lin et al., 2019). These findings illustrate that the eye of the yellowfin tuna, a frequently discarded portion, exhibits a notable concentration of hydroxyproline, comparable to that observed in the tissues or skins of marine species within the type (Thunnus) (Nurjanah et al., 2021).

3.2 Collagen concentration

The 8% pepsin treatment achieved a higher collagen concentration from the vitreous humor of yellowfin tuna (19.5% ± 4.59) than the 6% pepsin treatment (18.7% ± 2.04) and subsequently than the 10% pepsin treatment (17.6% ± 2.04) (Figure 4). Nevertheless, no statistically significant differences were observed between the treatments (P>0.05).

Figure 4. The percentage of collagen obtained with different pepsin concentrations. Equal lowercase letters (a) indicate no significant differences between treatments (P>0.05).

Figure 4. The percentage of collagen obtained with different pepsin concentrations. Equal lowercase letters (a) indicate no significant differences between treatments (P>0.05).

The collagen results were higher than those previously reported by Ahmed et al. (2019) with collagen concentrations ranging from 13.5% to 16.7% by pepsin-soluble collagen extraction from bigeye. Mafazah et al. (2018) reported a collagen yield of 12.5% from yellowfin tuna (Thunnus obesus) skins using alkaline extraction. In contrast, Chanmangkang et al. (2022) extracted collagen from the caudal fin tendons of skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) using acid extraction, achieving a yield of 7.88%. In contrast, Hema et al. (2013) reported collagen yields of 8.96% from dogfish (Scoliodon sorrakowah) skin and 4.13% from Rohu (Labeo rohita) skins using acid extraction. Meanwhile, Samiei et al. (2022) achieved a collagen yield of 17.3% from longfin tuna (Thunnus tonggol).

3.3 Yields

The extraction of collagen demonstrated similar yields across a range of pepsin concentrations. Nevertheless, the 10% pepsin treatment yielded a higher wet weight volume (4.8%) than the 6% pepsin (4.2%), 8% pepsin (4.3%) treatments. No significant differences were detected between the treatments (P>0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1. Collagen yields obtained from yellowfin tuna vitreous humor and comparison with other studies developed on fishery discards.

The application of 10% pepsin resulted in superior levels in terms of wet weight volume of yield obtained from the collagen vitreous humor of yellowfin tuna. This is due to the fact that pepsin acts by cleaving the cross-linked regions within the telopeptide without causing damage to the triple helix, thereby increasing the solubility of the collagen (Pamungkas et al., 2019). The results obtained demonstrated yields that were comparable to those reported in other studies, in which wet weight yields were also determined using a variety of extraction methods developed on discards and fishery by-products (Table 1).

3.4 Solubility and pH effect

The solubility of collagen was comparable between the 6% and 8% pepsin treatments. However, the treatment with a 10% pepsin concentration (P>0.05) exhibited a higher solubility (92.7% ± 0.15) and a lower collagen content (17.6% ± 2.04) compared to the other treatments (Table 2).

Table 2. Solubility obtained with different percentages of pepsin.

Acording to Duan et al. (2009) reported that the lower the collagen concentration the higher the solubility, this can be attributed to the effect of structural cross-linking on the degree of collagen solubilization, solubility increases when collagen molecules are weakly cross-linked. Therefore species that produce low amounts of collagen have a higher degree of cross-linking in relation to species that produce higher amounts of solubilized collagen the pH varied, obtaining the most acidic percentage in the treatment with 10% pepsin, which was the treatment that achieved the highest degree of solubility (92.7% ± 0.15) (Table 2). This is similar to that reported of Matmaroh et al. (2011) suggested by extracting soluble collagen with pepsin developed in goatfish (Parupeneus heptacanthus) scales, obtaining solubility percentages of 98% at very acidic pH (2.4). Other studies, such as Bae et al. (2008) reported that during the extraction of soluble collagen with pepsin in tiger fish (Takifugu rubripes) skins, maximum solubility (99%) was achieved at pH 3 concentration. Decreased immediately at pH 7, showing that pepsin-soluble collagen presented higher solubility at acidic pH, except at pH 10. As the elimination of the telopeptide regions could affect the protonation of the amino and carboxyl groups, this could affect the repulsive action of the molecules associated with the different levels of solubility associated with pH (Jongjareonrak et al., 2005).

3.5 Collagen protein composition

The Figure 5 shows the protein composition content of collagen obtained from yellowfin tuna vitreous humor at 3 pepsin concentrations.

Figure 5. Protein composition of vitreous collagen from yellowfin tuna. Same lowercase letters (a) indicate not significant difference between treatments (P>0.05)

Figure 5. Protein composition of vitreous collagen from yellowfin tuna. Same lowercase letters (a) indicate not significant difference between treatments (P>0.05) Yellowfin tuna eye is known to be good source of fat and protein with fat content 12.04% and protein concentration 10.17% respectively; it is a good source of major nutrients (Renuka et al., 2016). The study of Jayaweera (2022) regarding fat content in pepsin soluble collagen extraction reported similar values 4.18% ± 0.33 obtained in yellowfin tuna heads. The highest protein content of the extracted collagen was recorded in the 6% pepsin treatment (4.05 ± 0.03), followed by 8% pepsin with the highest percentage of fat (5.55 ± 0.04), and in lower percentage of volatile basic nitrogen in the 10% pepsin treatment (9.0 ± 0.02). The protein values were higher than those reported in the extraction of collagen in other marine species such as sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) (2.1%) (Santaella et al., 2007). Collagen extractions from fillet segments and scales of discards surpassed the protein levels obtained from the vitreous humor of yellowfin tuna. Ampitiya et al. (2023) reported 71.92% ± 0.43 collagen content in tuna skin. However, the nitrogen values from collagen extracted from the vitreous humor were lower than those found in the skins and muscles of other species, such as Basa fish (Pangasius bocourti) at 15.66% and bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) at 34.09% (Tran et al., 2023; Efrén et al., 2015).

3.6 Protein patterns

Two alpha chains (α1 and α2), with a molecular weight of 152 KDa (6%) and 109 kDa (10%), respectively, and one beta chain, with a weight of 157 kDa (8%), were observed (Figure 5). Additionally, bands below 100 KDa are visible, which may be indicative of collagen degradation. This suggests that during enzymatic extraction, some of the bands may be more susceptible to hydrolysis, which is consistent with the findings reported by Sotelo et al. (2016). The molecular weight of the protein in question falls within the range of 119 to 206 kDa. Other studies, such as that conducted by Shalaby et al. (2020) reported similar protein bands corresponding to molecular weights of 120 to 250 KDa, as observed in the extraction of collagen from scales and discards from tilapia (O. niloticus) and mullet (Mullus barbatus) fisheries. Montero and Acosta (2020) observed the presence of a 150 KDa protein in yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) skin gelatin, while Casanova et al. (2020) identified a 31 to 55 KDa protein in saithe (Pollachius virens) skin gelatin. Typically, two alpha chains and one beta chain are the defining structural characteristics of type I collagen derived from marine sources (Singh et al., 2011). Consequently, these findings collectively indicate that the collagen extracted from the vitreous humor of yellowfin tuna (T. albacares) is a representative example of type I collagen (Thilanja et al., 2018).

Figure 6. Molecular weight of collagen obtained from yellowfin tuna vitreous humor using SDS PAGE 16%, molecular weight standard (M), pepsin 6% (A), pepsin 8% (B), pepsin 10% (C).

Figure 6. Molecular weight of collagen obtained from yellowfin tuna vitreous humor using SDS PAGE 16%, molecular weight standard (M), pepsin 6% (A), pepsin 8% (B), pepsin 10% (C).

3.7 Amino acids composition

The amino acid composition of the collagen obtained from the vitreous humor of yellowfin tuna was derived from the treatment with the highest percentage of extracted collagen (19.5% ± 4.59). The results are expressed in milligrams per milliliter (Table 3). The most abundant amino acid in the collagen obtained was arginine, with a concentration of 5.422 mg/mL, followed by aspartic acid, with a concentration of 3.755 mg/mL. The values for glycine, glutamic acid, and serine ranged from 2.224 mg/mL to 2.161 mg/mL, while the remaining amino acids exhibited relatively low values. It is established that amino acids such as proline and hydroxyproline are integral to the collagen structure. The higher the amino acid content, the more stable the helices are (Ikoma et al., 2003). On the other hand, the amino acid composition showed interesting results compared to other research carried out on fish by-products in different species, where the total amino acid content for collagen extracted from vitreous humor ranged between 24.2% and presented certain variations with respect to that of collagens obtained in other studies (Table3).

Table 3. Amino acid composition mg/mL of collagen obtained from yellowfin tuna vitreous humor in comparison with other studies developed on different fisheries by-products.

4. Conclusions

The hypothesis was confirmed by the protein solubilization by pepsin which revealed the presence of collagen in the vitreous humor of yellowfin tuna. The application of acetic acid resulted in a higher percentage of solubility at a final pH of 3.8, as well as a higher hydroxyproline content compared to the other treatments. The analysis of the protein composition revealed the presence of primary nutrients and essential amino acids. In light of these findings, it is recommended to pursue a deeper investigation into the collagen-rich protein content of fish eyes. It is important to acknowledge that the eyes, along with the vitreous humor and the head, of yellowfin tuna are among the by-products that are commonly discarded during fish processing. The results of this study will contribute to the effective utilization of these underutilized resources

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as part of the project for the utilization of fishery waste, developed by the Faculty of Life Sciences and Technologies of the Universidad Laica Eloy Alfaro de Manabí. We extend our gratitude to the members of the research team and each of the technicians responsible for the laboratories where this work was carried out. We would like to express our gratitude to the municipal personnel of the fishing landing zone of the Esteros market for their invaluable assistance in the selection of specimens and the acquisition of samples.

Funding information

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Data availability

All available data are presented in the article.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: Jose Remigio; Data collection: Jose Remigio; Data analysis: Victor Oswaldo Otero; Figure preparation: Victor Oswaldo Otero. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and agreed to submit final version of the article.